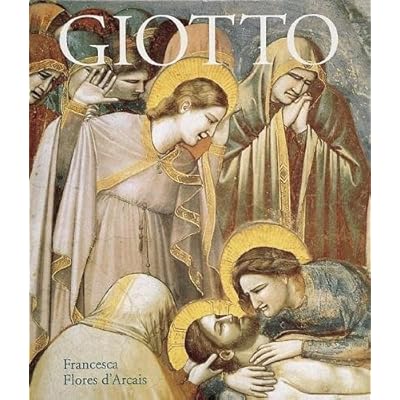

Giotto

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,History & Criticism

Giotto Details

Review “A magnificent book.” —Publishers Weekly“Giotto receives his due in what will be the standard book on his work for years to come.” —Booklist Read more About the Author Francesca Flores d'Arcais is a professor of art history at the University of Verona, Italy. An expert in the field of northern Italian painting, she has made numerous contributions to the study of medieval and Renaissance art over the course of her distinguished teaching career. Read more Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Preface to the Second Italian EditionFive years can be a long time for a figure like Giotto, who is the focus of ceaseless research that continuously enriches our understanding of his art, and encourages reconsiderations of it. Yet it has also been too short a time for these suggestions and stimuli, and indeed the maturation of this writer, to make a considered addition to what has already been said. For this reason, the 1995 text has been left substantially unchanged, with the addition only of the recent bibliography and this preface, which is intended to ex-amine the present state of Giotto scholarship, and in particular the catastrophic event that has recently affected his work, namely the earthquake of September 1997 and its aftermath.The past five years have in fact seen several new developments and critical studies that cannot be ignored. In terms of new attributions, the only one that I feel should be accepted without question consists of the two very beautiful little tondi depicting the half-figures of St. Francis and St. John the Baptist (below), now in a private collection, that were discovered by Luciano Bellosi (1997), who quite correctly assigned them to Giotto’s late period, circa 1320.I would also include among the critical acquisitions the panel with the Madonna and Child Enthroned from San Giorgio alla Costa in Florence (opposite). We can now examine this work in light of the excellent restoration carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, which at last allows us to fully grasp the grandeur of the painting’s construction, the fineness of its modeling, and its superb classicism.The practice, which has recently become common, of documenting restoration work with a small volume that, along with a historicocritical essay, also includes the results of the technical examinations and restoration, has given us a more precise knowledge of the techniques used by the master—almost, as it were, penetrating the work rather than only investigating its surface. Thus, for example, Giorgio Bonsanti, using reflectography, can assure us that “the author of the Madonna conceives of the image in three dimensions from the very first moment,” confirming the absolute and revolutionary newness of Giotto’s language, even in this early phase of his activity.But there are other restorations that, while not directly pertinent to Giotto, should also be considered, for they help us to better understand the environment in which he worked, and from which he drew ideas and inspiration. The recent restoration of the mosaics in the apse of Santa Maria Maggiore, which has brought back to life that luminous complex of gold, colors, and supremely beautiful lines, has given us a new awareness of the vivacity and richness of figurative art in Rome at the beginning of the last decade of the thirteenth century. Clearly the sophistication of Jacopo Torriti has little to do with the earthy power of Giotto’s volumetric approach, but it should be reaffirmed that this vision of a world of light must have profoundly influenced the young Florentine painter at the delicate moment of his transition from the very plastic and architectonic conception of form and composition represented by his work at Assisi, to one in which form softens into a more diffuse luminosity, as seen in the crucifix in the Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini (p. 123) and the Badia Polyptych (pp. 114–15), and in a clearer and more mature fashion in the frescoes in Padua.A second great restoration, that of the frescoes by Maso di Banco in the Bardi di Vernio Chapel in Santa Croce, and the extremely beautiful volume that resulted, can aid our understanding of the final phase of Giotto’s art. Now that we can fully appreciate the delicate and radiant beauty of these frescoes by one of Giotto’s foremost disciples, who perhaps assisted the master in his decoration of the chapel of the Castel Nuovo in Naples, we can better approach the problem of the “very sweet and unified” style that characterized Giotto’s own work in his final years of activity, as well as that of his disciples.As far as the critical literature is concerned, two new monographs have appeared that are essential to any reconsideration of Giotto, particularly as regards his training and early work, namely the frescoes at Assisi. In 1996, Bruno Zanardi published a large volume entitled Il Cantiere di Giotto. Le Storie di San Francesco ad Assisi, with an introduction by Federico Zeri. This book takes an entirely new approach, address-ing the problem of the Franciscan Cycle from a technical point of view, with the aid of diagrams of the giornate and photographic details that reveal how the frescoes were executed.Without going too far in terms of attribution—though he seems to incline toward the opinion of Zeri, who denies Giotto credit for the frescoes and hypothesizes Roman authorship—Zanardi nevertheless makes a fundamental contribution to our knowledge of the hands hat were at work in the Upper Basilica. On the basis of his technical analyses, he confirms the close unity of execution, and thus also the chronological continuity, between the scenes from the Old and New Testaments on the upper part of the walls, beginning in the third bay (and thus comprising the Stories of Isaac and Joseph on the north wall, those of the Passion on the south wall, and the Ascension and Pentecost on the counter-facade), and the Franciscan Cycle on the lower part. This means accepting the presence of a single master, who introduces his radically new language as early as the Stories of Isaac and then continues to the end (or nearly) of the decoration of the nave.The second important monograph is Luciano Bellosi’s Cimabue, published in 1998, just after the earthquake that damaged the Basilica of San Francesco. Its thorough analysis of the artistic language and development of this leading figure of the Florentine school also illuminates the impact of his teachings on the young artist from Mugello.As for Assisi, Bellosi’s exhaustive analysis of Cimabue’s paintings in the Basilica of San Francesco—which he assigns to a later date, in the papacy of Nicholas IV (1288–1292)—once again demonstrates the conceptual unity of the entire decoration, beginning with the transept and apse and continuing through the entire nave. The continuity of compositional struc-ture, and of the placement of the scenes within fictive architecture, specifically links Giotto to Cimabue, for example in the use of shelves seen in depth or in the Cosmatesque ornamentation.We should also mention two conferences that occurred in 1999: the first was held in the late spring at the University of Rome Torvergata, in honor of Ferdinando Bologna, and the second, which took place at Assisi on the second anniversary of the earth-quake, included, most significantly, a presentation—albeit in a preliminary form—of the results of the technical analyses that were carried out during the post-earthquake restoration.The earthquake, as is well known, struck the Basilica of San Francesco on September 26, 1997, destroying a not inconsiderable part of the frescoes in the upper church. Two zones of the ceiling were affected: toward the entrance, eight figures on the Giottesque Arch of the Saints (specifically, St. Peter Martyr, St. Dominic, St. Benedict, St. Anthony, St. Francis, St. Clare, St. Rufinus, and St. Victorinus), and the vela of St. Jerome in Giotto’s Vault of the Doctors of the Church; toward the altar, a star-studded vela in the first bay of the nave, and the vela of St. Matthew and Judaea in Cimabue’s Vault of the Evangelists.A heroic restoration effort was begun immediately, focusing first of all on the architecture, of course, and continuing with the restoration of all the frescoes in the Upper Basilica. On the improbably high scaffolding erected for their work—almost like a cathedral of iron within the vast, fractured space—a host of restorers have worked without interruption for two years to heal their great “patient.” At the same time, a group of experts have attempted to salvage some legible pieces from the innumerable fragments of painted plaster that were recovered after the earthquake. The first important result of this painstaking work was the reassembly of two figures from the Arch of the Saints, those of St. Rufinus and St. Victorinus, which were lifted back into place like a beacon of hope. Meanwhile, the walls and vault of the Upper Basilica were stabilized in just two years, making it possible to reopen the building to the public. Precise chemical and physical examinations were also carried out for the first time, in order to clarify the techniques employed in the execution of the various parts of the impressive decorative scheme; researchers sought to ascertain, among other things, the use of particular colors, the stratification of the applications of plaster, and the preservation of any sinopia or other preparatory drawings. As of this writing, these studies have unfortunately not yet been published, but the team from the Istituto Superiore per la Conser-vazione ed il Restauro has already presented some findings that will give us new insight into the problem of the Assisi frescoes.The close-up view of the frescoes afforded by the scaffolding has confirmed the substantial continuity of the cycle, from the transept and apse (and thus from Cimabue) through the entire nave, despite the succession of different workshops. This continuity is evident from the persistent presence of identifiable authors in both the upper and lower zones of the nave (as indeed Boskovits had already suggested), and from the repetition of decorative motifs in the framing of the episodes and on the intrados, in both the Cimabuesque vaults and the nave.This close viewing has also reaffirmed that the great technical innovations that took place during the execution of the cycle—beginning with the practice of working a giornate rather than a pontate, a transition that signifies the birth of true buon fresco (see p. 24)—coincided with the decisive change in style marked by the Stories of Isaac in the upper zone of the third bay. This underscores the revolutionary role played in the history of Italian art by the painter of these scenes, who for many critics, including this writer, may be identified with Giotto in his initial phase.Of course, the opportunity to study the frescoes at length from this new vantage point, including parts of them that might escape notice when viewed from below, has suggested other avenues of investigation that might add to our knowledge of their execution. For example, despite the apparent repetitiousness of the decorative bands that frame the scenes on the upper part of the walls and adorn the ribs of the vaults in the south transept, crossing, and nave, we can see that precisely in the bay with the Stories of Isaac, the plant friezes acquire a greater volumetric depth, and the rounded arches that embellish the ribs are replaced by arches rendered “in perspective,” beneath which are painted white canthari on a red ground, an obvious reference to classical ornament. This would seem to be another proof of the radical change of workshop that occurred in the upper part of the third bay. But in order to understand the frescoes’ relationship to “the antique,” we must also study the numerous insertions, almost always invisible from below, of small passages all’antica in the architecture of the Franciscan Cycle. These confirm Giotto’s persistent interest in the classical world, which he had certainly experienced firsthand in Rome prior to his arrival in Assisi.Another, more important issue is raised by a close examination of the Vault of the Doctors of the Church: we can see distinctly how the artist, painting these magnificent figures high up and on a concave surface, adjusted their proportions so that they would appear perfectly natural when seen from below. This method, which Torriti had already used slightly earlier in the Vault of the Four Intercessors, points to problems of perception that must have concerned all artists, certainly by the end of the thirteenth century. It would be worthwhile to investigate the precedents—both immediate and more distant—for this ability to construct images that take into account Read more

Reviews

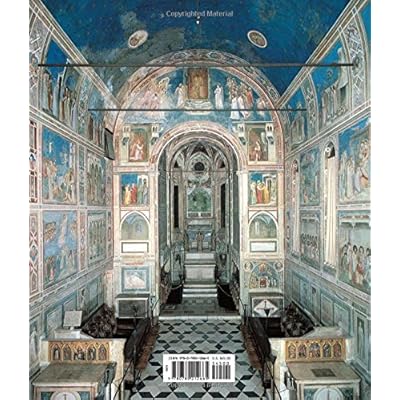

This book is a very high-quality addition to the literature on Giotto. The text follows both a chronological pattern and a thematic selection (with such themes as color or architecture in the master's works). In-depths studies of the famous cycles in Assisi (the St Francis Basilica, lower and upper), in Padua (the incomparable Scrovegni Chapel) or Florence (the Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce) are accompanied by thorough analyses of individual works and historical facts about Giotto's relationship with his patrons and his pupils. The illustrations are absolutely fantastic, with a profusion of magnified details and a rendereing of colors which is seldom found in artbooks.Highly recommended as much more than a beautiful coffe-table book.